Sustainability

Sustainability

An Unlikely Champion

If there is one thing Americans love, it is the comeback story. Winning can be boring, but winning after failing elicits something very primal in our nature. But life isn’t a Rocky movie; usually, the demons of addiction and depression end up destroying a person. There rarely is a made-for-TV ending, the musical montage with the smiling protagonist. Rather it’s just the simple tragedy of an unfulfilled life. But every once in a while there is a second chance, and not just the opportunity to win another fight.

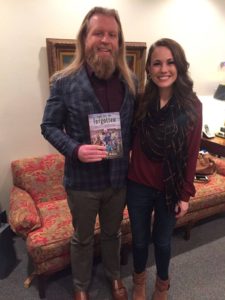

Justin Wren has an imposing presence. At 6’3” and 250 lbs, with long blonde hair and a blonde beard, he looks how you might imagine a Viking. There’s also an unmistakable athleticism to his gait that belongs to a man who’s used to fighting other people for a living. However, the warm smile and an easy demeanor instantly make you feel at ease. I sat down with him and his lovely wife Emily at a restaurant in Denver to learn about how a professional fighter ended up helping the Pygmy population in the Congo.

Wren was an all-American champion in wrestling and later started entering local fights to stay in shape while attending college. This launched a relatively successful MMA career. His professional record was 10-1 before being picked to be on The Ultimate Fighter, a reality TV show chronicling up-and-coming fighters in the UFC. Despite this success, the horrors of addiction began to take over Wren’s life. Precipitated by painkillers, the addiction began to manifest in many dark ways. For many elite athletes, what begins with taking highly addictive prescription painkillers, like oxycodone for injuries, spirals into a vicious addiction to alcohol and drugs.

“I was a drug addict…I was diagnosed with clinical depression, and my life just sucked for a long time even though, on the outside, things were going great. In that time, I had become a national champion in wrestling a couple of times and started fighting professionally, and the drug addiction and depression just got worse every time after I would fight,” Wren tells me.

He continued to win fights but slowly began to reach rock bottom. Hitchhiking through Colorado and staying in drug dens, battling thoughts of suicide, he was as lost as a person can be. Usually, this is where a story ends, one more statistic in a country of addicts. But Wren found religion, and it ended up helping him find a purpose to get sober. He’s not a missionary; his faith is rather private, but you can tell it gives him strength.

“And so my life really changed … I could skate over it, but, God help me, I started wanting to do something bigger with my life.” So, Wren started volunteering, seeking an outlet to help people and find a purpose after fighting. Wren came across the story of the pygmy population in the Congo. They are very small people — the average male is only 4’9” tall–who live in remote areas of the jungles. They face horrific treatment by the tribes surrounding them, including enslavement by the neighboring Bantu tribes, in a tradition that goes back generations. He decided he had to go visit these people and see if there was a way that he could help. What Wren he saw would change saw life forever.

He saw an enslaved population that had no options. He described seeing women carrying 120-pound bags of coal for an entire day, only to be paid with a scrap of goat meat. He also saw children dying of preventable diseases caused by a lack of clean water. “I even heard they were being cannibalized by the rebel groups around them, thinking they would become invincible in war if they could consume pygmy flesh because they were looked at as half-man, half-animal. Lots of superstition and different stuff like that. That’s been confirmed by the United Nations. I’ve met people that have watched family members be cannibalized.”

Wren decided that he had to stay and help these people even though it was humanity at its worst. “I went there, met them, fell in love with them, and just felt like I wouldn’t ever be able to go back to my fighting career…It was a better fight. Instead of fighting against a person, I got to fight for people, and I loved that because they accepted me into their tribe and village.”

Wren decided to start Fight for the Forgotten, an organization dedicated to emancipating the Pygmy population and building clean water infrastructure in these areas. It was difficult to start an organization like this from the ground up. However, he had the advantage of actually living and working with these people for an extended period of time, which gave him a level of insight that many NGOs never experience. This wasn’t some photo op; he actually lived with these people, sleeping on the ground of the twig huts in the jungle and eating their food.

There is a dirty secret to a lot of charity work in the Third World that often well-meaning people and organizations fail to listen to those they are trying to help. They build wells with no plan to maintain them or plan programs that may make sense from a boardroom in LA, but that simply doesn’t work on the ground. By becoming a part of the community, this former fighter recognized what was needed and how to accomplish it. Wren tells me that he avoided one of the biggest problems with freeing people from slavery, which is that by purchasing individuals’ freedom, you unintentionally end up creating a slave market. Wren avoided this by working with both the Pygmies and the other tribes to create a sustainable solution that wouldn’t just have the Pygmies fall back into slavery.

He explained it to me this way: “We bought back to land for a fair price and gave it to the pygmies. They benefit from having land for the first time, and the masters get the money. Then they both get clean water.”

The water became one of the key instruments for emancipation because the other tribes also lacked clean drinking water. By setting up a sustainable source of clean water, the tribes losing their slaves gained a vested interest in negotiating a deal not to enslave their neighbors again.

“I’ve seen some of the children pass because of dirty water, and it’s the toughest thing I’ve ever been through…And so to be able to come into a community and say both sides are going to have clean water, that means it’s going to save lives, it means their kids are going to live.”

As his organization expanded, he realized that he needed to involve partners with the experience to grow what he had created. He came across the organization Water4, which specializes in building long-lasting wells in Africa. “I emailed every single one of their employees on the website and said ‘I’m coming up. I’m going to knock on your door. Please train me.’” By partnering with organizations like Water4, Wren built Fight for the Forgotten into a lean, successful organization. Wren has already established 50 water wells and purchased 3,000 acres, on which large numbers of Pygmies now live.

Justin Wren has now returned to the ring to bring awareness t of a group of people halfway around the world. He’s won his first two fights, but the reality is he’s already a champion. He defeated drugs and alcohol and, in the process of finding himself, he found a voiceless group of people who needed a hero. He beams with pride when he tells me they call him “Efeosa Mangboa, the big Pygmy.” He gives all the credit to others with an innate humility. But this is a man who has freed thousands from the horrors of slavery, found faith, and met the love of his life, Emily. Hollywood couldn’t have written a better ending.

To get involved with Justin’s cause, please go to www.water4.org/fightfortheforgotten and donate. You can also purchase his book Fight for the Forgotten wherever books are sold.

Photos courtesy of Justin Wren.