Space

Space

Interview with Science Writer Leonard David

Innovation & Tech Today: What do we know about Mars so far?

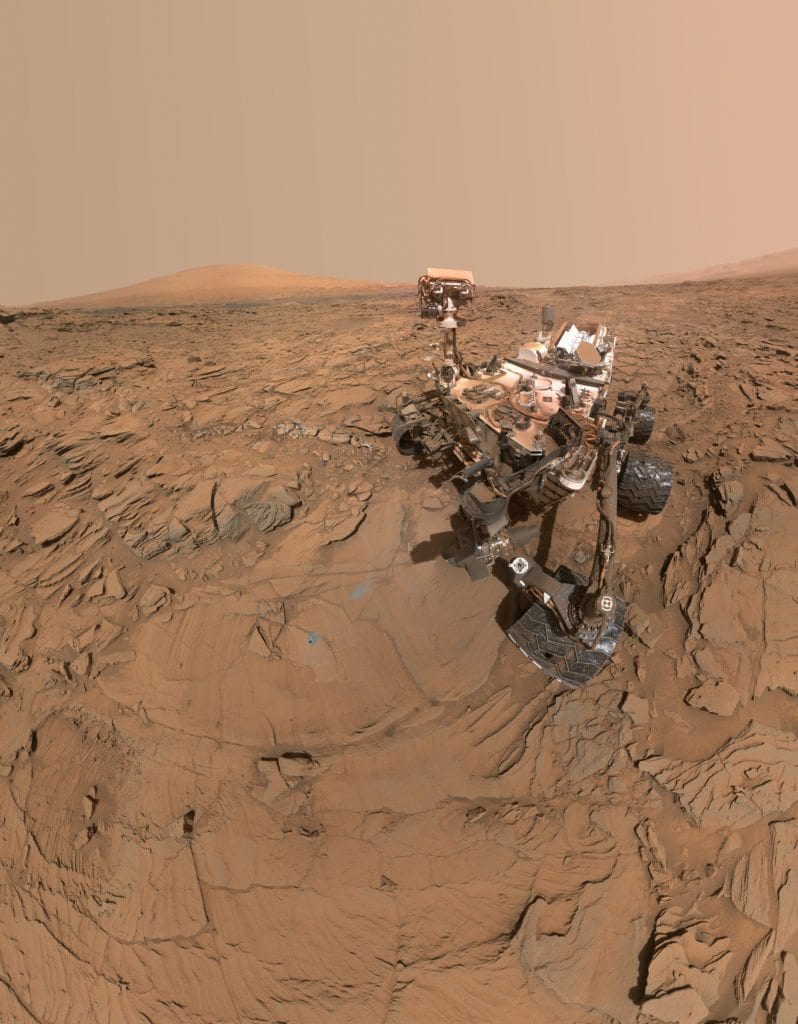

LD: Finding out about Mars has really turned out to be, I guess in a way, a “get to know me” planet. It’s on the other end of a lot of rovers, and probes, and fly-bys, and orbiters, and the amount of information we have now is pretty impressive, and even this morning I was on a website looking at the new Curiosity rover pictures coming in and it’s a place that looks to me like we’ve been before. It’s a lot of desert and dust, boulders and canyons. It’s kind of appealing in a weird visual way. Are we really going to go there and survive and thrive? Are we going to try and make it an Earth II kind of place? What’s the future going to be?

I&T Today: To you, why does Mars matter?

LD: It’s always been an interesting objective. I think in the book we talked about Percival Lowell somebody decades ago looking through telescopes in Flagstaff, Arizona trying to look at canals. People had visions of some kind of martians digging out canals trying to get the water down from the poles down to the cities.

It was always kind of populated. Even in the Walt Disney Tomorrowland television programs, they had what life would be like on Mars. Not our own life, but martian life. It’s always been a magnet kind of a place for thinking about what’s there; exploring, finding life, and then what do we do when we find it. A lot of that I tackle in the book.

I’ll tell you the weird thing that happened to me in this thing. I was at a conference last October, in Texas at the Lunar Planetary Institute. I went because it was the first landing site meeting for human crews, and they were bringing all these scientists together to say “Hey, we’re going to go, and where do we land?”

So you have hundreds of people who showed up to give their view on where to go. And that was pretty amazing to me, and that’s sort of what I tried to get in the book. This isn’t any more looking through the telescope wondering; the hardware is coming together, spacesuits are being designed, the habitats are under review about how big they could be, how you land these things. It’s got a lot of feel to it in the sense of reality.

Faulting on the surface of Mars (Image courtesy of NASA)

I&T Today: You had talked about psychological, sociological, physiological challenges. Could you go through what some of those challenges are and some of the possible ways we might be able to overcome them to make the mission work?

LD: I really wanted to make sure we didn’t have a book that just had a bunch of hardware. The whole psychological, physiological — that’s one of the reasons they’ve been launching long duration space flight in low earth orbit, to get a better understanding of the bone loss, and how you survive in a confined space. You’re talking about a flight of 6-9 months to get there and back another 6-9, maybe stay a year on the planet? Those are tough challenges. I allude to quite a number of problems that we are still wrestling with, whether it’s radiation, galactic ray bombardment, and then the well-being of the crew.

Who are these people? It’s not going to be a one-person thing. What kind of mix of occupations should you have? There are a couple of surprises in the book. I’m not going to go into them, but a few psychologists I spoke to…there are a lot of unknown unknowns [laughs].

When you go that distance, and you’re that far from everybody you’ve ever known, and your mission control is 20, 30, 40 minutes away, communications-wise… If you fall down and bust your helmet, it’s going to take a while for them to know that that happened.

And then there’s the ethical side. Obviously you’re going to go, and the potential to look for life is there. On the other hand, it’s also the question of “If we run into it, or we actually find it, what should we do with it? Should we even be near it?”

With scientists, Mars is sort of a second genesis of life, and you either don’t want to contaminate it or you don’t want it to contaminate you. My view is it’s there, it’s underground, microbial life, and it’s probably still very active.

I&T Today: Could you talk about how practical it would be to use the resources on the planet in order to survive?

LD: It’s a resource-rich world. There’s ice, other kinds of material you can use for construction. In the book, I get a little bit into the 3D printing fascination. It’s an evolving capability to use construction materials local and then carve out habitats. You can make bricks to start paving roads. Definitely the resources are there, but it’s still a mean place. There are chlorites on the surface; there are things that are dangerous: to live and learn to work in that environment, where it’s very hazardous to the first crews. My guess is we’ll be able to tame that and use some of the worst that Mars presents to our advantage.

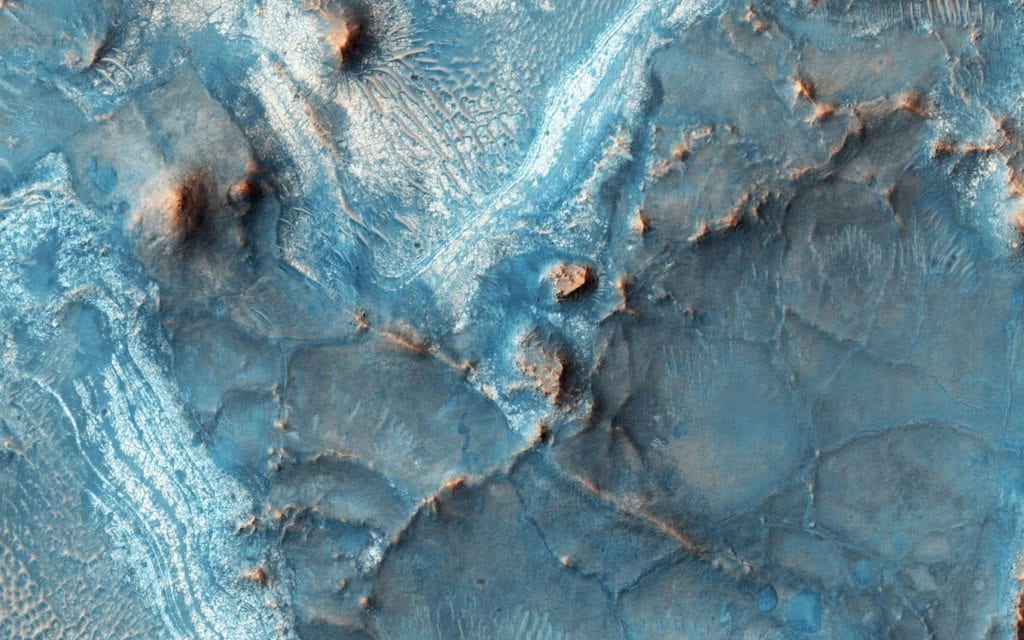

The Nili Fossae Region on Mars’ surface (Image courtesy of NASA)

I&T Today: Would you say that you’re confident we will be able to colonize Mars at some point?

LD: Yes. I did quite a number of interviews with some of the analog sites here on Earth. Analog means they’re simulating what a Mars facility would be like. You go to Antarctica, or you go to the North Pole complexes and you’re seeing what the early habitats would probably look like. You’ve got multiple crews coming and going, staying in larger and larger facilities with more capability to do science. This is no longer a pipe dream; people are working hard trying to come up with better hardware solutions.

But we still have some issues, and the one thing that can change all that is to get there faster. The technology is there, and there are people working on different types of propulsion systems, so who’s to say that the drudgery of Mars that we think of today won’t fall?

I&T Today: Do you think there’s anything with the Em Drive system that Eagleworks was developing?

LD: I’m not up on that one as much as I should be, but I read what everybody else writes and it still seems like it has pizzazz. In a few weeks I’m talking with Franklin Chang-Diaz, a former astronaut. He’s got the VASIMR engine that he’s working on. He’s talking weeks of travel time. But, again, it’s great to hand-weight those things as they’re putting them into space and seeing where we go. I just know that there’s no way transportation across space is not going to be faster than we know now.

There is a lot of chat about geoengineering Mars, where you terraform Mars. One of the arguments by one of the people I quote in the book is that we’re already terraforming on Earth, it’s just out of control. He’s a big climate change believer and he sees a lot of parallels between Mars. If we do it by accident down here, can we tame it and consider parts of Mars that might be selectively altered to support human life without spacesuits and domes and all kinds of facilities that will make living on Mars such a grander and less hostile place?

When somebody suggests something, at least when you have some sort of computational that looks like it’ll work on a test bed, well maybe they’ll stumble on something different, like on the Edison side with the phonograph record: make a mistake and serendipity takes hold from there.