Science

Science

The Martian Chronicles: Looking at a Future of Human…

In November 2016, an international crew of six astronauts will embark on a perilous journey to an unforgiving planet, extremely hostile to life, aboard the ship Daedalus. They will be humanity’s beginning towards exploring other worlds, as they seek to establish the first colony and life on Mars. Named after the Roman god of war, Mars will present a myriad of dangers that may align to kill Daedalus’ crew. If they succeed, they may position our species on a trajectory of interstellar exploration for the next millennia.

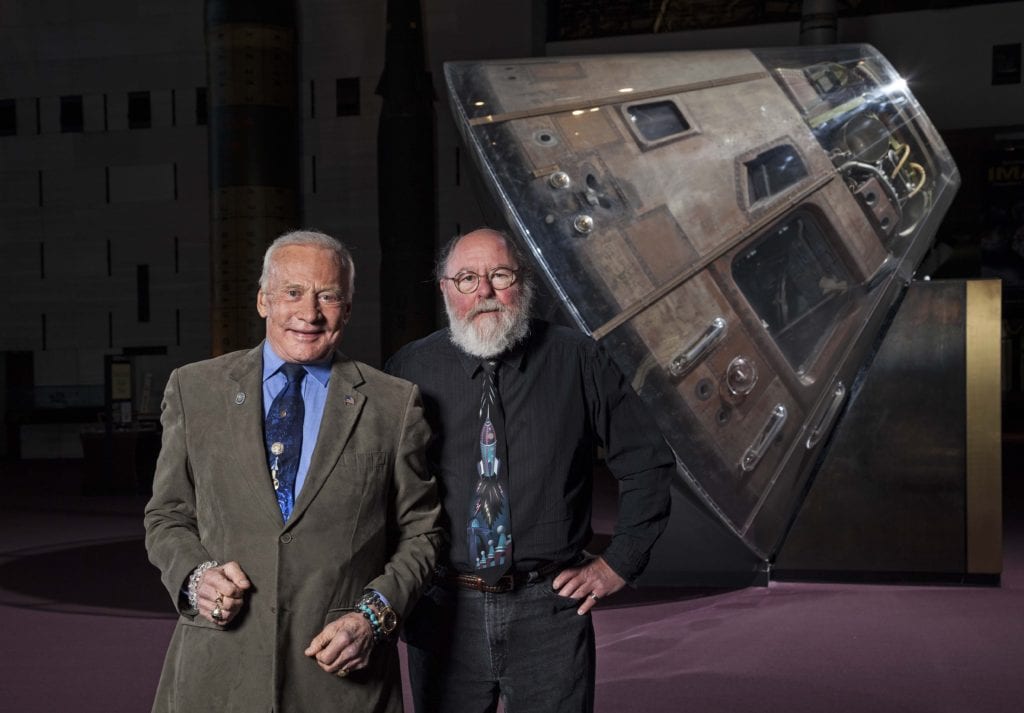

Unfortunately, this scenario is only fiction. The hotly anticipated six-part scripted mini-series Mars, from producers Ron Howard and Brian Grazer, will premiere on the National Geographic Channel in November. The series will follow the harrowing experience of a fictional team leaving Earth in 2033 to conquer the red planet. However, it does beg the question: How close are we to actually establishing a human colony on Mars? With Elon Musk of Space X debuting his Red Dragon rocket, slated for a 2018 launch to Mars, and the runaway success of the Ridley Scott film The Martian, the red planet has entered our cultural zeitgeist in an unprecedented way. I sat down with two of the most knowledgeable writers about Mars, Andy Weir and Leonard David, to get their takes on the viability and timeframe of a mission like this. David has been writing about space for over 50 years and is the author of the upcoming book Mars – Our Future on the Red Planet; Weir is fresh off his critically acclaimed debut novel The Martian.

“It’s difficult to justify sending humans to Mars. Why would you send a human to do a robot’s job?” Weir takes me a little off-guard when he asks me a question I don’t know the answer to. He laughs while explaining that it is vital, in his opinion, that we become a two-planet species in order to ensure our survival. He is cautiously optimistic that a colony could survive and prosper on the planet. “Mars has the four critical elements to maintain a biosphere: carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen. It has all of these in abundance. They would be able to grow that biosphere as large as they wanted,” Weir clarifies.

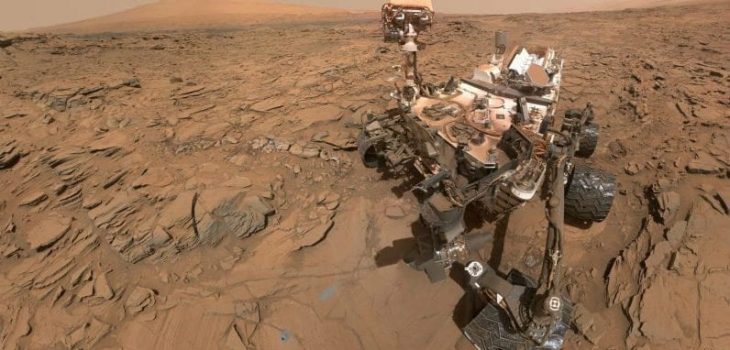

The viability of this mission has only been established relatively recently, as scientific expeditions like Curiosity have proven that the planet has a large amount of water in ice crystal form. This was vital for several reasons, the most obvious being that an infinite supply of O would be available for the future interplanetary explorers. Additionally, using the Sabatier reaction, carbon dioxide and water can produce methane and oxygen, which are the primary ingredients of rocket fuel. This would mean that instead of transporting enough fuel for a return trip, the Mars team could create sufficient fuel on the planet itself.

Although the feasibility of the project seems to be increasing, its enormous cost of represents a very real hurdle. I asked both writers what their opinions were on the rise of commercial companies like Space X, who are bringing the space race into the private sector. Author Leonard David, who has five decades of experience covering NASA, sees the possibilities of private companies alleviating some of these costs. “Elon [Musk] is already providing a tremendous boost to the space program. The private sector will sort of have to [absorb some of the expense], when you begin contemplating the costs this mission will entail. There are already public-private partnerships taking place all over the world, from China and Japan to India and Europe.”

Weir echoes this sentiment. “There will be no way to get to Mars without companies like Boeing and Space X. The competition with each other will drive the price down. If you have a no-bid contract with NASA to put a booster in orbit, you are not really motivated to come up with cost-cutting technology.” He points to the effect Space X has already had on the industry. “They’ve driven prices down so much. All the other manufacturers are scrambling to compete with Space X’s prices. We are at the very beginning of a real space industry.

Both writers are excited about the possibility that commercial space travel may become a viable experience for a middle-class person within the next hundred years and bring life on mars. Many experts believe that if the price of low-orbit boosters drops enough we could see a boom similar to the rise of the first airplane industry, which would in turn only drive down the price for this type of travel.

Despite the optimism, there are still cold realities that Earth’s first Martian explorers will face, primarily an extended trip that will place humans basically on their own, over 30 million miles from home. If anything goes wrong out there, it will be up to the crew to make repairs and find solutions in order to survive. They will then be living on a hostile planet that was never meant to support life. David brings up a point Buzz Aldrin, with whom he wrote a book, often makes: the thing we have to avoid with Mars is the “flags and footprints” approach that characterized the Moon landings. “We have to survive and thrive until we’re at a point where actual colonization can happen. It’s a resource-rich world. They’ll have to 3D print materials using Martian resources. But it’s a mean place. We’ll have to learn how to tame it, and use the worst that Mars presents to our advantage.”

Many people would argue that sending a mission to life on Mars is a useless exercise, a financial expense that makes no sense with the economic and environmental crises the planet faces. But that goes against who we are intrinsically as a species. Humans have always been curious as to what is over that next ridge, beyond the horizon of the ocean. From the Vikings to Christopher Columbus to the Apollo missions, we have always been explorers. Life on Mars is only the next in a long line of explorations. The difficulty of the mission isn’t a negative; rather it’s why we yearn to do it in the first place.