security

security

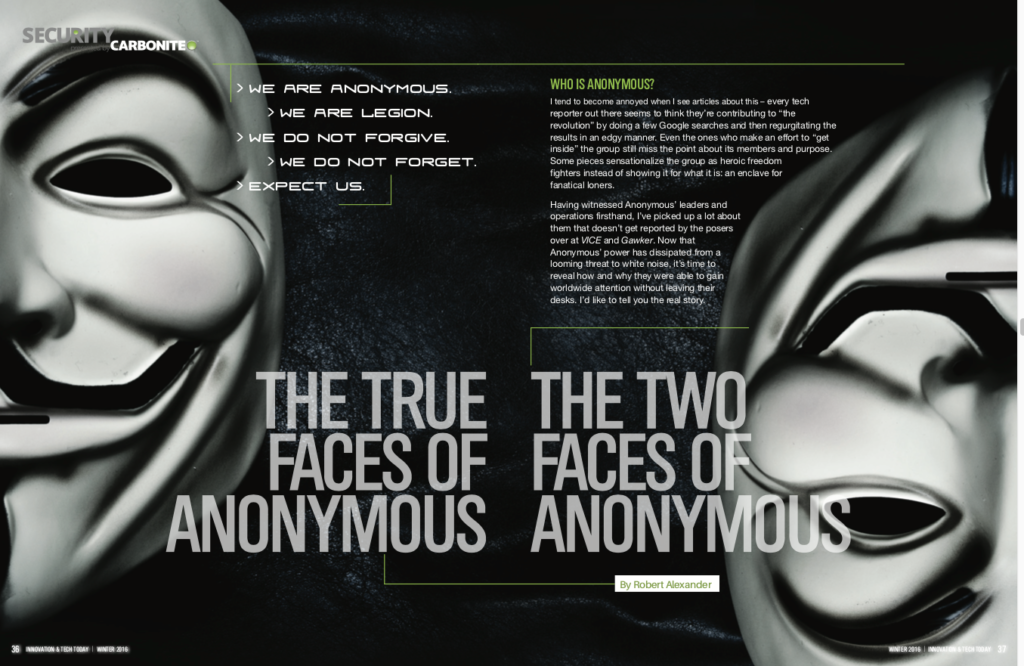

The Two Faces of Anonymous

Who is Anonymous?

I tend to become annoyed when I see articles about this – every tech reporter out there seems to think they’re contributing to “the revolution” by doing a few Google searches and then regurgitating the results in an edgy manner. Even the ones who make an effort to “get inside” the group still miss the point about its members and purpose. Some pieces sensationalize the group as heroic freedom fighters instead of showing it for what it is: an enclave for fanatical loners.

Having witnessed Anonymous’ leaders and operations firsthand, I’ve picked up a lot about them that doesn’t get reported by the posers over at VICE and Gawker. Now that Anonymous’ power has dissipated from a looming threat to white noise, it’s time to reveal how and why they were able to gain worldwide attention without leaving their desks. I’d like to tell you the real story.

I spent the majority of my adolescence on internet relay chat (IRC). IRC is a good platform for internet-based communication because it’s minimalist (requiring little processing power) and provides a degree of security and anonymity. It’s also a great place to meet a wide variety of criminal types, including drug traffickers, assassins, con artists, and, obviously, hackers. It wasn’t too long after assimilating into IRC that I started making friends associated with notable hacker groups, including Anonymous. At some point in 2010, I first joined what was called the AnonOps IRC network, which had become the hub of Anonymous’ operations around this time due to the group’s attacks on Amazon, PayPal, and financial institutions. I was already well aware that the group was being used as a cover of sorts for “real” hackers, but I stuck around to see how their efforts would unfold.

The Beginning of a Movement

Anonymous has always had two masks — divided between doing good and terrorizing the internet. Anonymous originated on 4chan, the largest and oldest English-speaking imageboard (a forum focused on the sharing of images, like a weird precursor to Instagram). The default username on 4chan is “Anonymous,” and it was originally used to refer to the collective of 4chan posters in a way that addresses all of them at once — i.e., “Hey Anon, I have a problem with my website and need your help.”

The first interaction Anonymous had with the rest of the internet was through their raids (some would call them pranks) on other websites. The group reached its first major turning point when they disrupted the podcast belonging to white supremacist Hal Turner. Initially, the Hal Turner raids were conducted just for fun, but eventually an ethos developed that, because they were targeting a major figure in the white supremacist community, Anonymous was for once doing the right thing. A year later, Anonymous declared war on the Church of Scientology following the church’s attempted censorship of a video interview with Tom Cruise. Anonymous dubbed their war on Scientology “Project Chanology,” and for the first time began to organize protests in major cities (although Anonymous organized in real life as early as 2007, when 4chan users across the world showed up at various Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows book launches to share spoilers of the book that had been leaked online with eager fans).

The most significant byproduct of Project Chanology was that Anonymous had gained worldwide attention in major news outlets for the first time. However, the newly found niche of Anonymous in the media as “hacktivists for good” would annoy many of Anonymous’ early members who believed the group should stay dedicated to trolling. While the “good” Anonymous was protesting Scientology, the troublemaking Anonymous was posting flashing GIFs to the Epilepsy Foundation’s website and harassing the family of McKay Hatch, the 13-year-old founder of Nocussing.com. Many of the affiliates I knew that had histories working for Anonymous maintained themselves as trolling groups. Some managed the most popular invasion (/i/) boards where Anonymous planned these raids; others were members of the Patriotic Nigras, another Anonymous offshoot that disrupted the popular online game Second Life. It seemed that many of the members and contributors were trying to preserve the spirit of the old trolling Anonymous, in an era when Anonymous had transitioned from being hated to praised by most internet users.

Rise of the Hackers

While Anonymous defined itself as an anarchistic group without established leaders, the reality is that, during their heyday (roughly 2010-2012), a handful of “real” hackers working under the Anonymous name controlled the collective. It’s important to note that most Anonymous members knew little to nothing about computer security, which left the “hacking,” and thus the direction of Anonymous, up to those who did.

Furthermore, the leaders of Anonymous lacked credibility with wider hacking scene. Most hackers hold a fairly negative view of Anonymous: they’re seen as either laughable or annoying, and are by no means welcomed in traditional hacker circles. This meant that whoever was going to do the dirty work for Anonymous had to be motivated in some way to attack the systems of major corporations and governments under the banner of a group that would earn them no money or respect from their peers – leaving power as the only motive for a skilled hacker to support Anonymous.

Some of these leaders would eventually form LulzSec, a splinter group of Anonymous that made headlines by compromising the websites of major media outlets. Interestingly enough, the majority of Anonymous/LulzSec’s hackers lived in poverty as they championed the group. And if it wasn’t poverty, it was something else. Famous hackers like Sabu lived in Section 8 housing, while Commander X was homeless, Ryan Cleary hadn’t left his bedroom in years, and Barrett Brown was addicted to heroin. For many of those in control, Anonymous was no more than a distraction from the miserable life surrounding them.

The rest of Anonymous, the non-hackers idling in chat rooms, saw it very much as a revolutionary group. They would spend hours chatting with each other, discussing the impending collapse of various world governments at the hands of Anonymous, the oppression of the one percent, and police brutality while eagerly awaiting one of the higher-ups to announce their next big hack.

Whenever the leaders of Anonymous would run into trouble attacking a target (or didn’t feel like actually doing anything themselves), they always had the option to militarize the few thousand enthusiastic 16-year-olds willing to follow their every command. A good example is the usage of LOIC (Low Orbit Ion Cannon). LOIC is a simple program that allows one to execute a denial-of-service attack. Basically, think of it like trying to drink from a fire hose, except the water is data and you are a server. Get enough kids to point their LOIC clients at the same IP address and you have enough power to take down a website.

Another asset of having so many people at one’s disposal is that there’s a large pool of individuals far more likely to get arrested for such activities than you are. The leaders of Anonymous eventually developed a tactic where a gullible Anonymous regular would transfer illegal information (though usually misinformation) to individuals suspected of being informants to see the response. One example is a young woman using the handle “N0” on AnonOps — aka Mercedes Haefer, who was featured prominently in the documentary Hacker Wars. “N0” was given network privileges, but only to bait the feds into raiding her home in 2011, giving Anonymous a clear red flag that the government was onto them.

An Army of the Vulnerable

Anonymous’ lesser members were often living in situations similar to that of the hackers they admired. Most were teens in difficult family straits, and playing the role of therapist was extremely common. Regulars on the network would share their life struggles in public channels in a way that could be best described as fishing for sympathy. This tactic would typically work, though, and eventually AnonOps hosted channels dedicated to non-Anonymous topics such as transgender support and homelessness to provide emotional aid to its members. I would attribute much of the loyalty Anonymous’ members had to this community-building. The purpose most Anonymous members thought they’d find by joining what they saw as an insurgency somehow transformed into friendships. It wasn’t uncommon either for romantic relationships – or more often than not hookups – to start on AnonOps from time to time.

However, Anonymous, and by extension AnonOps, was still largely under the control of the more elite LulzSec crowd. Their internal communication was different than that of the casual Anonymous members: there were no discussions regarding politics, government oppression, or fighting for “good” to prevail. Rather, they’d focus on potential targets and rival hacker groups. What began to complicate the leadership of Anonymous was the fact that there would always be non-Anonymous hackers hanging out in the Anonymous backchannels as well. These were usually friends of LulzSec hackers wishing to contribute privately, though on occasion there’d be certain individuals invited to the channel whom Anonymous was hoping to impress.

At times, Anonymous was no more than a means for the hackers, as well as their friends, to publish compromised information under a name that wasn’t directly affiliated with them. Compromised data or information related to hacks would usually flow from LulzSec and affiliates to trusted AnonOps members, and then to Anonymous’ “press team” (the aforementioned IRC users usually set up to take the fall), who would publish info on Pastebin and Twitter. The end result of most of Anonymous’ big hacks was AnonOps patting themselves on the back for their contributions to the fight against tyranny while the hackers responsible celebrated their own power to intimidate corporate, financial, and/or governmental powerhouses while keeping the blame focused on Anonymous.

Government Backlash

Having someone chatting with you online and then abruptly disappearing because they were arrested is an uncanny experience. Someone you know (or as much as you can “know” someone through lines of text over the internet) will be actively talking and then suddenly disconnect without any warning – you usually figure out that they were busted within 20 minutes to a few hours of the raid. Depending on your relationship with the individual, his arrest can range from hilarious to terrifying. The one feeling I’ve always experienced in these types of situations is a certain sense of connectedness shared between the internet and the real world that I don’t usually acknowledge. There’s no better way to understand that everything you do online is still part of the same physical world than having the realization that someone you knew was just taken into federal custody for doing something stupid on the internet.

One of the most memorable arrests for me was that of Ryan Cleary. Ryan was about 20 and was also a pretty huge deal in “the scene” at the time. I knew Ryan somewhat well and liked him a lot, mostly because of his love for eagerly destroying anything or anyone on the internet that he saw fit. In real life, Ryan was extremely autistic and apparently rarely left his bedroom in his mom’s basement, which I’m sure explains the online aggression to some degree. Nonetheless, Ryan’s attacks against the MPAA, the U.K.’s Serious Organized Crime Agency, and the British Phonographic Industry, among others, were instrumental to the success of Anonymous’ Operation Payback. I was on his network when he was arrested[1] in June of 2011, which caused a good deal of panic — mostly a fear that the governments of the Western worlds were finally closing in on these pesky hacker groups (and they were).

Final Days

Following the arrests of most LulzSec, AnonOps, and other major Anonymous members and cohorts in 2011-2012, Anonymous as a whole began dying out. The skilled hackers were gone, and nobody wanted to fill their places for fear of another federal crackdown. There are still active Anonymous groups, and AnonOps is running once again (by whom I have no idea), but it seems unlikely that Anonymous will ever attain the same infamous status they had during the Payback/LulzSec era. People might also just be giving up on the idea that any web-based group could trigger a social revolution, since, realistically, not much came of Anonymous’ efforts. It did show that we live in a society in which thousands of misguided young people are willing to dedicate their lives to a hacker group they thought they’d find some kind of fulfillment in, and that there are people just as willing to manipulate this group to their advantage. That’s the real story. Anonymous was not some mythical group of vigilantes righting the world’s wrongs. Just some lonely kids looking for a real connection in a digital world.

[1] Ed. Note: Ryan Cleary was arrested on child pornography charges in 2011. He was convicted, and later released in 2013.